Copyright 2018 by Gary L.

Pullman

Horror writers with

longstanding records as bestselling authors are not exempt from

writing novels with unsatisfying endings. When the novelist is

Stephen King, whose novels typically run as many as eight hundred

pages (sometimes more), an unsatisfying ending is more than annoying;

it's horrible.

Many of King's novels do

end poorly, as It, Under

the Dome, Revival,

and many others attest. After reading hundreds of pages in which

reality seems fairly real (other than the presence of the

centuries-old, shape-shifting “It”), only to discover that the

universe isn't a product of the Big Bang, as astronomers apparently

mistakenly believe, but that it resulted from a gigantic turtle's

need to vomit—well, readers are apt to think the effect is anything but agreeable. In fact,

readers might think they'll be sick enough themselves to vomit a

universe of their own. Likewise, the ending of Under

the Dome is beyond

frustrating. After plodding through hundreds of pages (many of which are

devoted to King's Democratic progressivism and his obsessive hatred of

Republicans and of President George W. Bush and Vice-President Dick

Cheney in particular), readers discover that the invisible and

impenetrable dome that cuts off Chester's Mill, Maine, is the result

of a gigantic, mischievous female adolescent alien who placed an inverted dome over the town, much as a mischievous

Earthling might invert a bowl over an anthill. Consequently, readers are likely to

work out until they've acquired sufficient strength to rip this

ridiculous novel page from page. While writing Desperation,

King seemed to find nothing amiss with the views of Christian

fundamentalists. He even sought out one of them, a pastor, as his

adviser. But, as The Regulators,

the companion novel to Desperation,

indicates, King likes to turn

the tables on himself. He does just this in Revival.

He'd had no problem with the beliefs and teachings of Christian

fundamentalists when he wrote Desperation,

but, while writing Revival,

he said he couldn't stomach the Christian fundamentalists' idea of

hell, as it's described in the Bible. He doesn't cite chapter and

verse, but here are a few passages,

from the King James Version of the Bible, concerning hell, that most

Christian fundamentalists would probably accept:

For a fire is kindled in mine anger, and shall burn unto

the lowest hell, and shall consume the earth with her increase, and

set on fire the foundations of the mountains (Deuteronomy 32:22).

The sorrows of hell compassed me about . . . (Samuel

22:6).

Yet thou shalt be brought down to hell, to the sides of

the pit (Isaiah 14:15).

And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast

it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members

should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell

(Mathew 5:29).

And fear not them which kill the body, but are not able

to kill the soul: but rather fear him which is able to destroy both

soul and body in hell (Matthew 10:28).

And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon

this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not

prevail against it (Matthew 16:18).

Ye

serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of

hell? (Matthew 23:33).

And if thy hand offend thee, cut it off: it is better

for thee to enter into life maimed, than having two hands to go into

hell, into the fire that never shall be quenched (Mark 9:23).

And in hell he lifted up his eyes, being in torments . .

. (Luke 16:23).

For . . . God spared not the angels that sinned, but

cast them down to hell, and delivered them into chains of darkness,

to be reserved unto judgment . . . (2 Peter 2:4).

According

to these verses, hell, an expression of divine wrath, is a locked pit

below the earth. Made of several layers, it's a place of eternal darkness

and everlasting fire, in which the damned, who are cast therein

bodily, are beset by sorrows and live in constant torment (although

both body and soul can be destroyed in hell). It's occupied by both

fallen angels and by human sinners, and it's set against the kingdom

of heaven, which shall overcome it.

This

is the conception of hell that King finds ridiculous. In its place,

he offers something so extremely absurd that it's laughable, and it

is with this, his own conception of hell, which he believes is

superior to the Biblical depiction of hell, that he concludes

Revival,

describing hell as a gigantic anthill full of gigantic, ravenous

ants. Huh?

Somehow,

King sees a huge anthill in which huge ants crush sinners with their

huge jaws as superior to the depiction of hell provided in the Bible,

the King James Version of which

is, without argument, one of the greatest literary masterpieces of

the English language. With judgment this poor, it is truly a wonder

that King ever managed to write his much better, earlier work.

The

endings of the stories by Bentley Little, another prolific horror

novelist, are as bad as those of King's worst books. They're

tacked-on, rather than being integral to the plot, and, typically,

they explain nothing concerning what has transpired in the hundreds

of pages preceding them. They seem to hint at an explanation, but, as

there is no actual explanation at which to hint, the intimation itself is nothing more

than a half-hearted, meaningless gesture. Read virtually any of

Little's novels, including the one for which he won the dubious Bram

Stoker Award, and you'll see what I mean—but be prepared for a

major disappointment. For example, The

Resort

suggests the bizarre incidents which occur at the present resort are

somehow linked to those which occurred at an earlier, nearby resort,

which now lies in ruins. How and why the two resorts might have

shared some common causal link is unclear because unexplained.

Therefore, readers are within reason to assume that there never was

such a link. Likely, they will feel cheated of the time, effort, and

money they spent in reading the novel.

Horror

master Edgar Allan Poe offered a solution to the dilemma of the

sloppy ending 172 years ago. In “The

Philosophy of Composition” (1846), he explains how he wrote his

narrative poem “The Raven.” First, he decided how the story would end. Then, he selected

everything—every word, every image, every figure of speech, every

point of the plot, every character, every line of dialogue, every

nuance of the setting—so that the final result, the story's effect,

would be inevitable, given what came before and led up to it. It

seems clear that neither King nor Little (nor many other writers, of

the horror genre and of other genres, have any idea where their

stories are going or why, but write only in the moment, making up the

plot as they go.

Poe

applied his technique not only to “The

Raven,” but to most of his stories and other narrative poems.

One story for which the ending isn't as clear and fitting as the

conclusions of his other tales is “Ligeia.” As Kevin J. Hayes

points out, in The

Annotated Poe:

The

ending leaves many questions unanswered. The reappearance of Ligeia

can be interpreted as a phantasmagoric illusion [an image projected

by the so-called magic lantern, a type of early projector], an

opium-induced hallucination [the narrator uses laudanum], a

psychological fantasy, a modern recurrence of a traditional

transformation legend, or an actual event. . . .

Comments

Poe made concerning the story's problematic ending indicate that he'd

intended the story to have a supernatural ending. A friend of his,

Pendleton Cooke, asked about the story's resolution. In response, Poe

“suggested how he might have improved it”:

One

point I have not fully carried out—I should have intimated that the

will did

not perfect its intention—there should have been a relapse—a

final one—and Ligeia (who had only succeeded in so much as to

convey an idea of the truth to the narrator) should be at length

entombed as Rowena—the bodily alterations having gradually faded

away.

It

seems that Poe, unlike King, Little, and a host of other writers,

learned his lesson about writing sloppy endings. He was careful, from

then on, to plan more carefully the outcomes of his stories, the vast

majority of which have the unified structure and the single effect

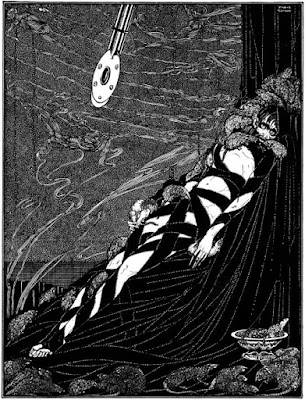

for which he has become famous. For example, “The Pit and the

Pendulum” is based an article, “Anecdote towards the History of

the Spanish Inquisition.” According to this article, “when

General Lasalle entered Toledo, he immediately visited the Palace of

the Inquisition,” where he tested a torture device, which he found

to be in good order.

As

Hayes observes, the way in which the article recounted the story was

ineffective from “a dramatic point of view,” so Poe reversed its

chronology:

Though

fascinated by the story, Poe nevertheless recognized what was wrong

with it, at least from a dramatic point of view: it was backwards. By

having Lasalle arrive in the first sentence, the article destroys all

possibilities for tension and terror. Poe turned the story around,

describing what happens to one particular prisoner while saving

Lasalle's timely intervention for the final paragraph.”

Poe

had learned the lesson that he would teach in “The

Philosophy of Composition” and exemplify in the majority of his

own short stories, essays, and narrative poems: in the words of the

bard, “All's well that ends well.”