copyright 2008 by Gary L. Pullman

Adam Smith, alive

In Chapter 1 of Part I (“of the propriety of Action”) of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith makes a number of statements of interest to writers of fiction, horror and otherwise. He finds pity or compassion to be natural emotions, present even in “the greatest ruffian,” and considers the basis of these sentiments to be the individual’s ability to project him- or herself into the situation of another by means of an imaginative identification with the other’s plight. Such sympathy, he contends, is the “source of our fellow-feeling” regarding both the “misery” and the “joy” of others.

The examples that he offers in support of his view are often such as would warm the heart of the horror aficionado. For instance, he argues that the suffering, both physical and emotion, of a victim who is being tortured upon the rack remains inaccessible to an observer: “as long as we ourselves are at our ease, our senses will never inform us of what he suffers. They never did, and never can, carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations. . . . It is the impressions of our own senses only, not those of” the other’s “which our imaginations copy.” In short, to each individual, everything is all about oneself, even one’s identification with another’s misery or joy.

Smith’s view is in keeping with the theory that fiction, whether it takes the form of narrative poetry, the short story, the novel, or drama of the stage or screen, is based upon the premise that the reader or the viewer--the audience--identifies, imaginatively, with the plight of the protagonist, or the main character, experiencing the action, as it were, through this character’s eyes and ears and enjoying or enduring, as the case may be, his or her experiences.

One who doubts this contention, Smith says, has proof of it in the way that people imitate the actions of those with whom they have formed an imaginative association. Observer will witness a man draw back his hand or limb when it is about to be chopped off, he says, and the observer will likewise snatch his or her own hand back. A crowd, observing a hanged man, will jerk their bodies in imitation of the hanged man’s paroxysms, he adds. Something similar is true when, seeing a body falling from a height, we might add, the observer averts his or her gaze, not caring to see the terrible moment of impact, although, of him- or herself, the observer feels nothing real; he or she merely imagines what such a collision would feel like, were the observer in the place of the unfortunate person who is falling. Moreover, Smith avers, the more vivid the sight--the gorier or the more ghastly, the horror writer might suggest--the greater the emotional effect it has upon those who are mere observers of another’s plight.

Applying these principles to drama, Smith contends that we are joyful at the “deliverance of those heroes of tragedy or romance who interest us” and are grateful “towards those faithful friends who did not desert them in their difficulties; and we heartily go along with their resentment against those perfidious traitors who injured, abandoned, or deceived them.” In other words, readers bond with sympathetic characters, liking those who assist them and disliking those who harm or neglect them. (By “sympathetic,” we do not necessarily mean a character of whom the reader is fond; rather, a sympathetic character may be one whom the reader likes--but the sympathetic character may also be one who, although disliked, is understood or one who is intriguing in some way. Of course, a character with too many negative traits, or with even a single negative trait that is extreme and significant enough to overwhelm his or her positive traits, will not be sympathetic, even if he or she is both understood and intriguing.)

Smith believes that sympathy is a result more of situation than of the display of emotion, as is seen by the fact that an observer may feel an emotion, such as embarrassment, by observing someone who, although behaving rudely, is not embarrassed him- or herself.

His observation seems to suggest, when applied to fiction, that Aristotle was correct in assigning greater value and importance to plot than to character--or, at least, to the emoting of characters. The living’s ability to identify with the dead (or their idea of the dead) seems to be the clearest demonstration that sentiments are reflections of the self’s responses to imagined situations. After all, the dead feel nothing, but we, the living, imagine how we would feel if we were in their place, but sensate, rather than insensate: “the idea of. . . dreary and endless melancholy. . . arises altogether from our joining to the change, which has been produced upon them [death, decay, dissolution, being forgotten] our own consciousness of that change, from putting ourselves in their situation, and from our lodging. . . our own living souls in their inanimate bodies.” The “dread of death,” or, more precisely, the fear of nothingness, mortifies humanity, but it is a “great restraint upon the injustice of mankind. . . guards and protects society,” Smith suggests.

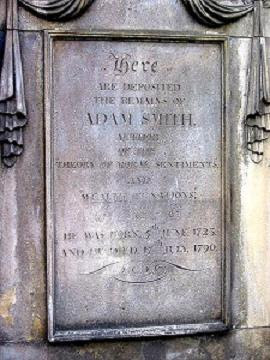

Adam Smith, dead

His description of “the dread of death” is worth quoting at length, because of its implications for writers of horror (and other) fiction:

We sympathize even with the dead, and overlooking what is of real importance in their situation, that awful futurity which awaits them, we are chiefly affected by those circumstances which strike our senses, but can have no influence upon their happiness. It is miserable, we think, to be deprived of the light of the sun; to be shut out from life and conversation; to be laid in the cold grave, a prey to corruption and the reptiles of the earth; to be no more thought of in this world, but to be obliterated, in a little time, from the affections, and almost from the memory, of their dearest friends and relations. Surely, we imagine, we can never feel too much for those who have suffered so dreadful a calamity. The tribute to our fellow-feeling seems doubly due to them now, when they are in danger of being forgot by every body; and, by the vain honours which we pay to their memory, we endeavour, for our own misery, artificially to keep alive our own melancholy remembrance of their misfortune. That our sympathy can afford them no consolation, seems to be an addition to their calamity; and to think that all we can do is unavailing, and that, what alleviates all other distress, the regrets, the love, and the lamentations of their friends, can yield no comfort to them, serves only to exasperate our sense of their misery. The happiness of the dead, however, most assuredly is affected by none of these circumstances; nor is it the thought of these things which can ever disturb the profound security of their repose. The idea of that dreary and endless melancholy, which arises altogether from our joining to the change, which has been produced upon them, our own consciousness of that change, from putting ourselves in their situation, and from our lodging. . . our own living souls in their inanimate bodies, and then conceiving what would be our emotions in this case. It is from this very illusion of the imagination, that the foresight of our own dissolution is so terrible to us, and that the idea of those circumstances, which undoubtedly can give us no pain when we are dead, makes us miserable when we are alive.

Edgar Allan Poe uses this tendency of people to project their own emotions--and their consciousness--upon others, including inanimate corpses, to great effect in his horrific short story, “The Premature Burial,” in which a man, buried alive, experiences what we, the living, imagine would be the horror of the grave, were we, yet alive, to be put in the place of the dead.

The body may be corporeal and earthbound, but, through the imagination, the mind, or soul, becoming all things, transcends time and space, to reach out and beyond, and to assume the forms of rocks, insects, plants, animals, other human beings, or the gods themselves. In horror fiction, as often as not, the soul also descends to the level of the demonic, exploring the underworlds of Hades and hell. The monster, we find, is ourselves--but it is only one aspect and one avatar of ourselves. We are the three worlds--the world of the divine, the world of the earthly, and the world of the diabolic. By showing us what is horrible, horror fiction shows us, also, what is good; by demonstrating the worthless, horror fiction shows us, too, what is worthwhile. As such, in the face even of death and nothingness, horror fiction is a guide to the

good life. Life and, indeed, existence-itself, is all about us, but, paradoxically, at the same time, nothing is about us. Were it not for fiction, pantheism would be necessary, for we are protean, and we would populate all things and nothing.

In future posts, we will consider other ways in which Adam Smith’s views are, at times, at least, something of a hermeneutics for horror fiction.